Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, and story-telling apes

I’ve been reading, and focusing on AI. In the fiction area, Gnomon is a complete mind-melt. One of the many premises of the book is that a “system” will run society. If Then

takes it a step further, positing a system that runs multi-variate testing on communities to optimize itself.

In the popular science range, the best description of AI I’ve found is <a target=”_blank” href=”https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/0141979240/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1634&creative=6738&creativeASIN=0141979240&linkCode=as2&tag=kuytcom-21&linkId=d330230d01aa2851262ec78dac65513e”>The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World</a><img src=”//ir-uk.amazon-adsystem.com/e/ir?t=kuytcom-21&l=am2&o=2&a=0141979240″ width=”1″ height=”1″ border=”0″ alt=”” style=”border:none !important; margin:0px !important;” /> – an intelligible history of machine learning and AI.

I listened to this You Are Not So Smart podcast on how biases are baked into AI, and what we might do about that.

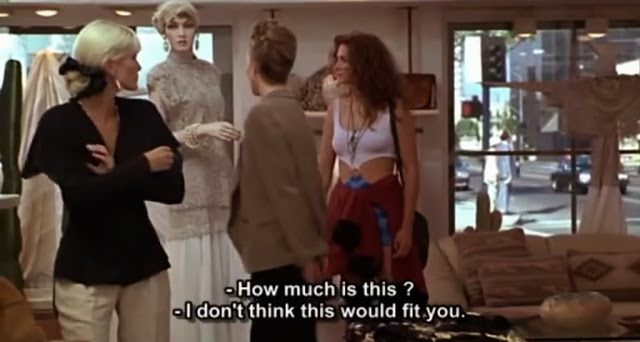

And most recently, I’ve read this description of an online retailer’s efforts to predict whether a user will be profitable, based on all the attributes that retailer knows. It’s probably the state of the art in this sort of thing – it’s a fairly general problem, there online retailers have lots of data, and getting it right has big financial pay-offs. Instinctively, it feels right – a shop keeper recognizes signs that a customer might spend a lot of money, and knows that treating high value customers better will make them even more valuable. Though they get it wrong – remember the scene in Pretty Woman? A sex worker, acted by Julia Roberts, goes into an expensive boutique, and the shop assistants size her up and discourage her from shopping there; it’s only when the sex worker’s client (Richard Gere) shows up and they recognize his spending power that they treat her like a valued customer.

The fun bit is to see how hard this problem is, and how the economics work.

The paper describes a few ways the retailer has approached the “how can we predict the value of a customer” question. They’ve created over 130 different attributes, and looked for which ones were most predictive. Those 130 attributes sound like a lot – but many of them are really simple, like “how many orders have you placed”, “how often do you place orders” etc. And with those 13o attributes, they get fairly good results – around 75% accurate.

The second part of the paper describes how they’re trying to include “self-learning” algorithms, that look at all of the data they have, and use it to create a better prediction. The website tracks everything you do – surely, there must be a correlation between looking at certain products and spending more money (there is) – so how do you let the algorithm work that out?

It turns out to be possible, but the cost of training the system to find these behavioural correlations on fast-moving product catalogues is high – and with AI, that cost is often measured in money, not just time.

What does that mean?

It means that the AI would apply a statistical model to Julia Roberts’ web traffic, and unless she matches one of those 130 attributes they use to predict her life time value, the AI would assume she’s “just another customer”. However, if she then browses the expensive, high-fashion dresses category and spends a lot of money, the AI would not learn that customers who look at expensive, high-value customers are likely to spend a lot of money.

Why is this interesting? Because a state-of-the-art machine learning system, with significant commercial incentives, cannot economically learn to identify behaviour triggers without human intervention.

It boils down to “using traditional methods, we can consider perhaps a handful of attributes to predict your lifetime value. Current machine learning allows us to expand that to hundreds of attributes. But to learn from the thousands of subtle clues each of us leaves is currently orders of magnitude too hard”. It’s the difference between categorizing you by crude methods, less crude methods, or treat you like an individual.

And this brings me to the second topic here – human intelligence is very much tied up in story-telling. Sure, humans can manipulate symbols and abstractions, and use formal logic to prove or disprove things. But explaining phenomena in the real world is largely story telling. There’s an example I read somewhere about a finance editor on the TV news explaining the stock market behaviour, and using exactly the same underlying fact to explain opposite trends – something like “positive figures on the labour market lead to higher stock prices as the market anticipated stronger consumer spending”, and “positive figures on the labour market lead to lower stock prices as the market anticipated a rise in interest rates to curb inflation”.

If you read the academic paper on customer lifetime value prediction, the authors do some story telling – “it makes sense that high value customers look at the more recent products, because they are more fashion conscious”. Story telling apes observe things in the world – the rising of the moon, an erupting volcano, a pattern in the data – and we tell stories to explain those things. As we’ve built better models of the world, the stories have become more accurate (and therefore more useful); many stories have become quantifiable and predictable – we no longer believe the sun rises because a deity drags it across the sky on a chariot; instead we can calculate to the second what time the sun will rise thanks to Newton’s formulae.

So what is the point of this long-winded musing?

Whilst ecommerce sites are non-trivial, they are certainly not the most complex system you might imagine when considering the uses of artificial intelligence. And they have relatively clear outcomes, within a meaningful timeframe – you buy something or you don’t, and you usually do it within a fairly short time of visiting the site. And even at this scale, we struggle to identify actions that correlate cleanly with the outcomes using current machine learning techniques. We need story-telling apes to at least identify hypotheses for the A.I. to test.

If you try to expand the scope of AI to “look at human behaviours, and anticipate health outcomes”, or “anticipate criminal behaviour”, or “anticipate political choices” – we’re still a long way off.